The name of this blog is the ‘Little Netsuke’. But what is a netsuke? This article will answer that question. We’ll review the art that inspired the name, its history, evolution and cultural importance.

Let’s begin with the most basic facts of pronunciation and meaning. For English speakers unfamiliar with Japanese, the natural inclination is to stress the ‘u’ and pronounce the final ‘ke’ as key. In fact, the true pronunciation softens the ‘u’ almost until it’s inaudible, while the final ‘e’ sounds like that in elephant.

The kanji used to write Japanese words often hint at the word’s meaning. As is the case here. 根付 is a combination of root (ne) and attach (tsuke). As we will see this may point to their origin.

Now armed with this basic knowledge lets continue further into the world of netsuke.

What is the purpose of netsuke?

The compound root-attach, suggests its function was to attach something to something else. This was exactly their purpose. To be more accurate, a netsuke was one part of a system that allowed items to be carried while in traditional Japanese dress.

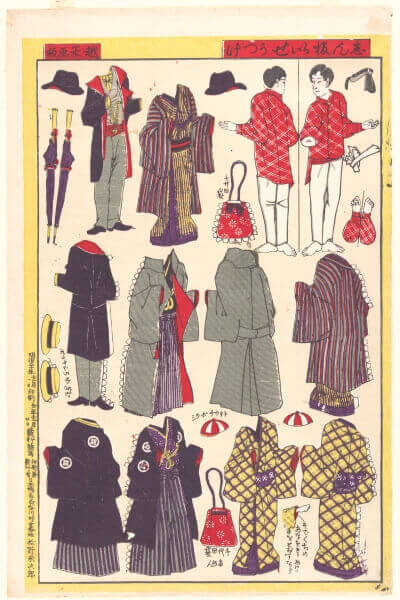

The kimono was key to the creation of netsuke. That is because a kimono and other traditional Japanese clothing, have no pockets. So, alternative methods of carrying everyday items on one’s person was needed. There were three primary methods in use.

The most natural solution was to store things into the amble sleeves or generous breast folds of the kimono itself. Though simple, this method has obvious drawbacks and limitations. Next, you could tuck items under the sash (obi) of the kimono. Though this also doesn’t seem to be ideal it’s an improvement on the first. The final solution was to hang items from the obi (sash). This solution needed netsuke.

To succeed in hanging items from the obi, you needed several elements, a container, cord, a netsuke and a toggle.

The container (inrō) was a box made up of several sections stacked one-on-top-of-the-other. A channel along the side of the container allowed a cord to be threaded through. The cord was then passed through a toggle (ojime) and at the top of the loop through a hole in a netsuke. The cord would return through the ojime and down the other side of the inrō (container).

Knotting the cord underneath created a loop with the inrō at the bottom, netsuke at the top and ojime (toggle) in the middle. Ready for use, the loop was passed under the obi and the netsuke hooked over the top edge of the sash (obi).

The great strength of this system was that, by drawing the toggle towards the tiered container the sections could be secured together. Alternatively, moving the toggle up loosened the inrō, allowing access to its contents. Thus, a person could use the inrō while the loop hung in place.

In this way, it was more convenient to carry items in this way than secreting them any which way around the garment. Netsuke were a small, but essential part of this carrying system.

How did they develop?

Once again, the compound root-attach is telling us more. This time about origin. The character for ‘root’, refers to the roots of trees or plants, so it seems reasonable to surmise that the first netsuke were simple found objects. A small pebble, a smooth stick or a piece of worn root would be simple to find and repurpose for the job.

However, this supposition is not just based on logic. The forms of the main types of netsuke are evidence for this theory. The three main types are sashi, manjū and katabori.

Sashi netsuke, take their name from the Japanese verb sasu, meaning to insert. They are carved sticks with a lip or hook at the top. The stick was inserted under the obi (sash) and hooked over the edge by the lip. Their origin as a simple stick found at the side of the road seems believable to me.

Next, the manjū netsuke. They take their name from the traditional Japanese rice cake, as they are similar in shape. Again, it hardly seems fanciful to imagine the manjū netsuke starting life as a small round stone from a beach or riverbank.

Right: Saka-Manjū by funny face on Shutterstock.com

Finally, the most recognisable form today; the katabori netsuke. These so-called sculpture netsuke are carved in the round. Once more, I can well image a small knot of wood or root being smoothed off and used as a netsuke.

While the name and shapes of the major groups of netsuke point to their early origins, this does not explain their evolution into what we know today. For this we need to look at the history of the Edo era.

How did they evolve?

The Eda period (17th – late 19th century) was important for netsuke as this period was their heyday as functional objects. During this period they became the intricately carved objects we can see in museums today. But this development did not come about by accident, but by the unique social circumstance of Edo Japan.

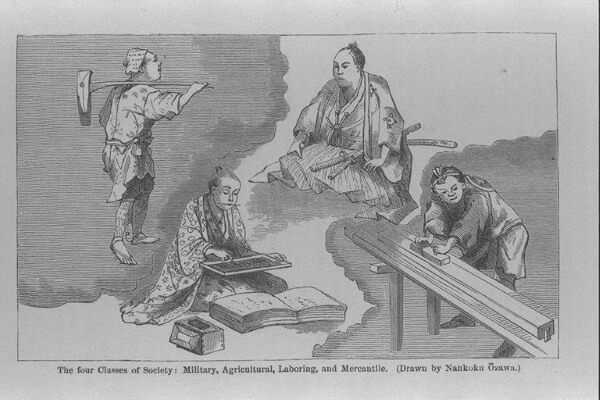

In the Edo period, Japanese society was split into a rigid class system (Shinokosho). At the top stood the samurai class, followed by the farmers, then artisans and merchants at the bottom. This social system was based on the groups contribution to the community. Samurai provided protection and governance and farmers fed the population. But merchants made money from others work, not producing anything themselves.

However, though the merchants’ social status was poor, they were rich in financial terms. This is where Edo period sumptuary laws come in. To prevent the low status rich from displays of wealth not befitting their social standing, fashion was policed. Therefore, the chōnin (artisans and merchants) had to live according to their social rank, rather than their financial means.

In step the inrō and netsuke. These rather small, functional objects allowed the chōnin to circumvent the material laws and provided an outlet for the display of financial success. As inrō and netsuke took on the role of wealth symbols, a whole industry was born.

Competition between customers and between craftsmen drove netsuke to become ever more intricate and well-crafted. An art was born.

How did they survive?

It wasn’t all smooth sailing, though. In the 19th century netsuke had a problem. The existence of these objects was based on their function, not just social symbolism. So, they were vulnerable to changes in society and the needs of the people. The opening of Japan brought both.

Already in decline at the beginning of that century, as tucking pouches under the obi gained favour, Westernisation threatened the netsuke with complete annihilation. As more and more Japanese laid aside the kimono and took up the suit, the presence of pockets ended the day-to-day need for these objects. Thus, the humble pocket almost doomed an entire artform.

However, netsuke’s doom and their salvation came hand-in-hand. Contact with Japan ignited a fascination with all things Japan. The Western enthusiasm for Japanese objects included netsuke and so provided a whole new market for them.

Famous figures such as Rudyard Kipling, Peter Fabergé and many besides became avid collectors. In fact, in the late 19th century and early 20th century the collection, study and appreciation of netsuke was a Western pursuit.

Right: Fabergé Snail (20th century) courtesy of V&A, London

But the basis for netsuke had changed. Western patrons had no interest in the original function of netsuke. For them, they were art. This completed the shift from simple function to complex art secured the netsuke’s future.

There are still exhibits in countless museums around the world. Though, that is not to say that it is a dead artform, preserved behind museum glass. It lives on today and it is important that it does.

Why are netsuke important?

The gifts of inspiration and fascination that netsuke give are important, but I think it goes further than that. Netsuke are important as a focus of conversation and collaboration between Japan and the rest of the world.

The Western collectors of the 19th century saved the netsuke. Then, in the second half of the 20th century, Japanese craftsmen and scholars rediscovered this artform. Therefore, while steeped in the culture of Japan, there is some sense of a joint ownership of the artform.

At the beginning of the last century, there were Western scholars and Japanese creators. At the end, there were Western and Japanese creators and scholars alike. A fact underscored by the creation of the International Netsuke Society.

Cemented as an international artform, netsuke are a medium of communication between Japan and the world. Their unique history gives rise to a feeling of joint ownership, which invites a more equal collaboration. No longer split between Japanese creator and Western collector, netsuke form a common ground between different cultures.

Conclusion

As mesmerising objects with a fascinating history, the netsuke story is rich. From simple roadside objects, to symbols of wealth and then international artform, it is a compelling journey.

For me, this is why netsuke are special. In the beginning they enchant, then invite you to explore their origin, at last bringing you into a dialogue with Japan and its culture. All this is achieved in an unassuming and modest way. What could be more Japanese?

Sources

- Hutt, J, 2012, Japanese Netsuke, V&A, London

- Benson, P, 2010, The Art of Netsuke Carving, GMC Publications

- Milhaupt, T.S, 2009, Netsuke: From Fashion Fobs to Coveted Collectibles, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nets/hd_nets.htm)